In a move that underscores the delicate and politically charged nature of its investigation, the Madlanga Commission has confirmed that its interim report will not be released to the public. This decision, while potentially frustrating for transparency advocates, is a calculated procedural step with significant implications for the inquiry’s integrity and ultimate outcome.

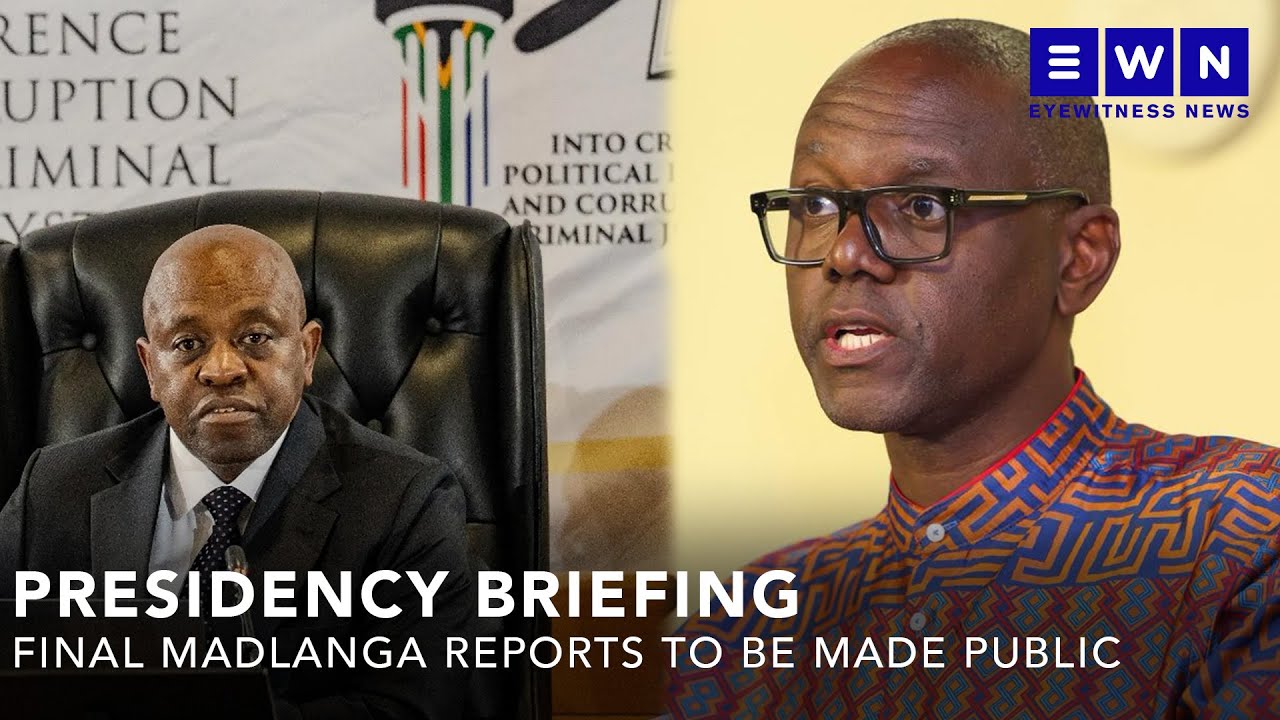

The commission, formally known as the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Maladministration, Corruption, and Related Matters within the South African Police Service (SAPS) in KwaZulu-Natal, was established in the wake of extraordinary allegations leveled by Provincial Police Commissioner, Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi. His claims, which have been described as “explosive,” reportedly involve high-level political interference, procurement irregularities, and systemic corruption within the province’s police service—allegations that strike at the heart of the SAPS’s credibility and governance.

The decision to keep the interim report confidential is not an attempt to suppress information, but rather a standard and often necessary practice in judicial or quasi-judicial inquiries. Interim reports are typically submitted to the appointing authority—in this case, the President—to provide a progress update, outline preliminary findings, and potentially request extensions of time, additional resources, or expanded terms of reference. Public release at this stage could jeopardize the ongoing investigation by allowing witnesses to coordinate testimony, evidence to be tampered with, or subjects of the inquiry to apply political pressure. Furthermore, premature publication could unfairly prejudice individuals against whom allegations are made but who have not yet had a full opportunity to respond.

This veil of secrecy, however, exists within a critical tension. South Africa has a recent history of state capture inquiries, where public hearings played a vital role in building national awareness and trust in the process. The balance between operational confidentiality and public accountability is therefore paramount. The commission’s final report, which will contain definitive findings and recommendations, is legally required to be made public. The interim phase is about building the case, not presenting it.

The allegations themselves, as hinted by the limited public information, suggest a crisis of leadership and governance within a key provincial police structure. If proven, they would point to a severe breakdown in the chain of command and the independence of the police from political actors. This context makes the commission’s work not merely an administrative audit, but a fundamental test of the rule of law. The careful, methodical, and protected process leading to the final report is designed to ensure that its conclusions are based on irrefutable evidence, capable of withstanding legal challenge and political scrutiny.

For the public and observers, the key metrics of the commission’s credibility at this stage are not the contents of the interim report, but its actions: the thoroughness of its witness summons, the robustness of its evidence-gathering, and its resistance to external influence. The commitment to a transparent final disclosure will be the ultimate measure of its success. Until then, the withheld interim report serves as a reminder of the high stakes involved—a silent indicator of the complex and potentially damaging truths being unearthed behind closed doors. The path to accountability often requires a period of confidential scrutiny before a moment of public reckoning.